Khalili Collections / CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/deed.en, via Wikimedia Commons

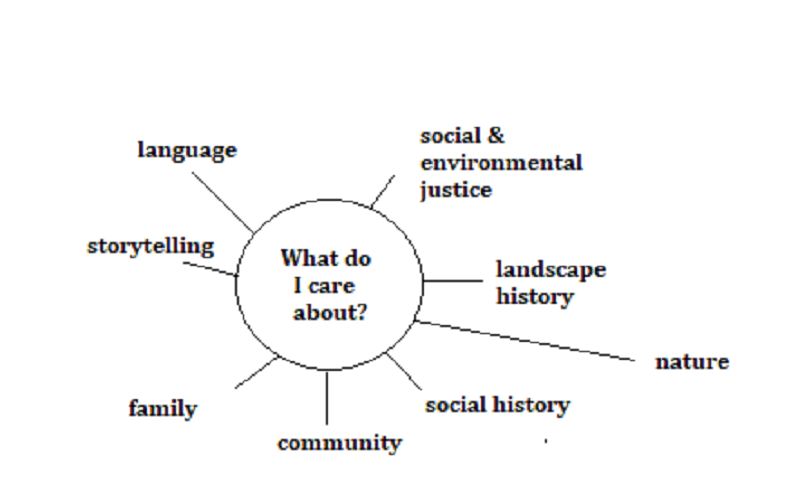

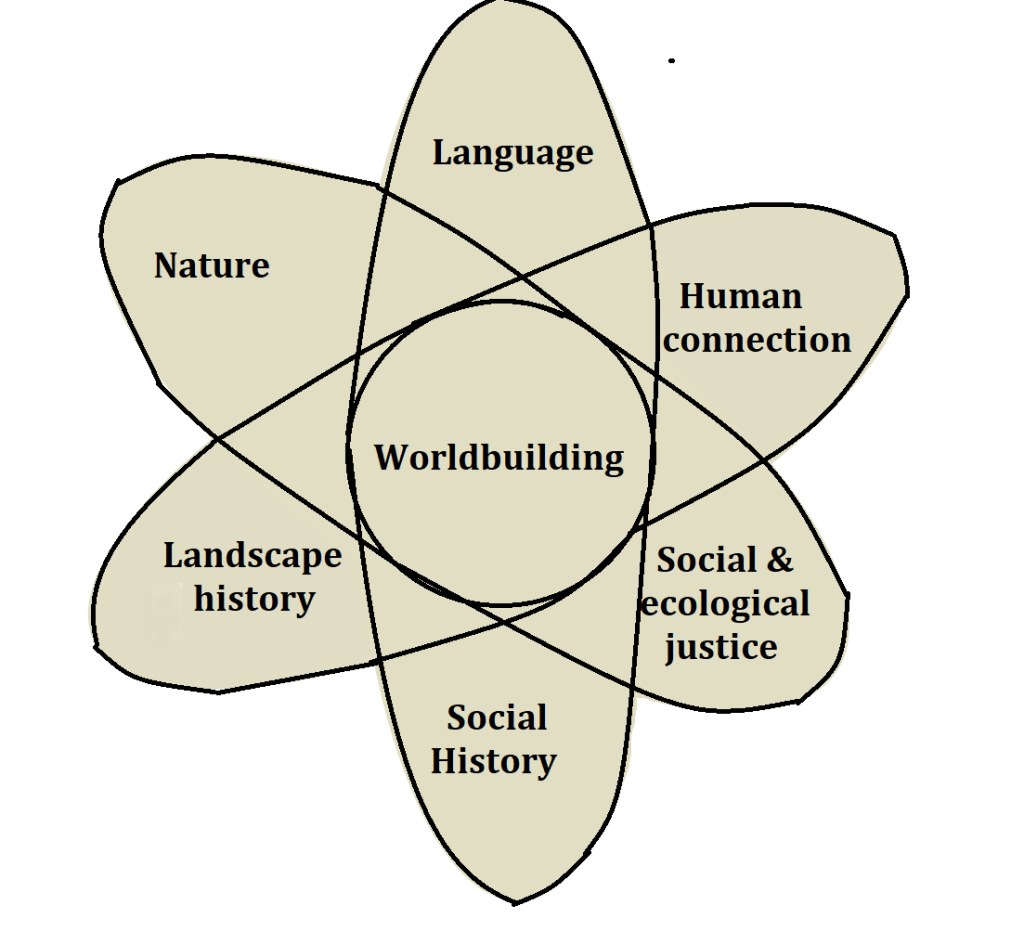

Inspiration and understanding can come from the most unexpected sources. In my other blog, which focuses mostly on writing – mine and others’ – about the natural world, I mentioned, a week or two ago, that I was reading a collection of essays about landscape and place called Going to Ground. One of these essays is by Amina Khan, on the link between Islamic writing about nature and the Romantic movement in English poetry and prose.

My fictional world isn’t ours, but I can’t pretend it isn’t based on ours, and in the cultures I’m writing about, trade with my equivalent of North Africa and the Middle East is an important part of the story. In an earlier instalment of this series, I wrote about my youngest point-of-view character, Audun, and his love for the sea and sky and saltmarshes of Torrey, where he grew up. Audun is seventeen, academic, and of course he’s written some juvenile poetry.

Audun, being who he is, is expected to travel, to learn more of the world before he enters a life of teaching, his dream being to eventually be the head of my equivalent of a medieval university. His great-uncle, whom he hopes to emulate, spent a few years in his youth travelling east, gathering histories, settling down to a life of translation and comparison with the histories of the west. Luce, his aunt, is a doctor, much of her learning done in eastern lands as well.

But what Audun was going to learn in those travels (outside of life lessons, of course) I didn’t know. Until I was showering today (why do ideas so often arrive in the shower?) and my mind made the connection between Audun’s love for nature and the Islamic writing Amina Khan described in ‘A Wild Tree Toward the North’, her essay in Going to Ground.

Organized religions don’t exist in my books, replaced by philosophy and personal faiths in a wide range of deities. But religious writing can also be read for its poetry, and that’s how I’ll approach this. The bonus here is I’ll read some poetry that I probably wouldn’t have otherwise, and my world, like Audun’s, will expand.

You must be logged in to post a comment.