A Guest Post by Stephanie Churchill

The Masterworks Blog Tour

How many of us have wandered through an art gallery and daydreamed about a painting that catches our eye or an intriguing sculpture on the plinth? I definitely do. So the idea of coming up with a short story based on this premise didn’t require me to consider for long.

I had been researching Mesopotamia, particularly the foundation of the Akkadian Empire, when I learned about the discovery of the Bull-Headed Lyre of Ur. I have been trying for several years to write a work of fantasy using the Akkadians as an anchor for the setting of my fictitious world, but the final form of that book has been elusive. When I was invited to write a piece of short fiction, I realized that using this lyre would be a great way to use my research on the Akkadians even if my longer novel is proving difficult to finish.

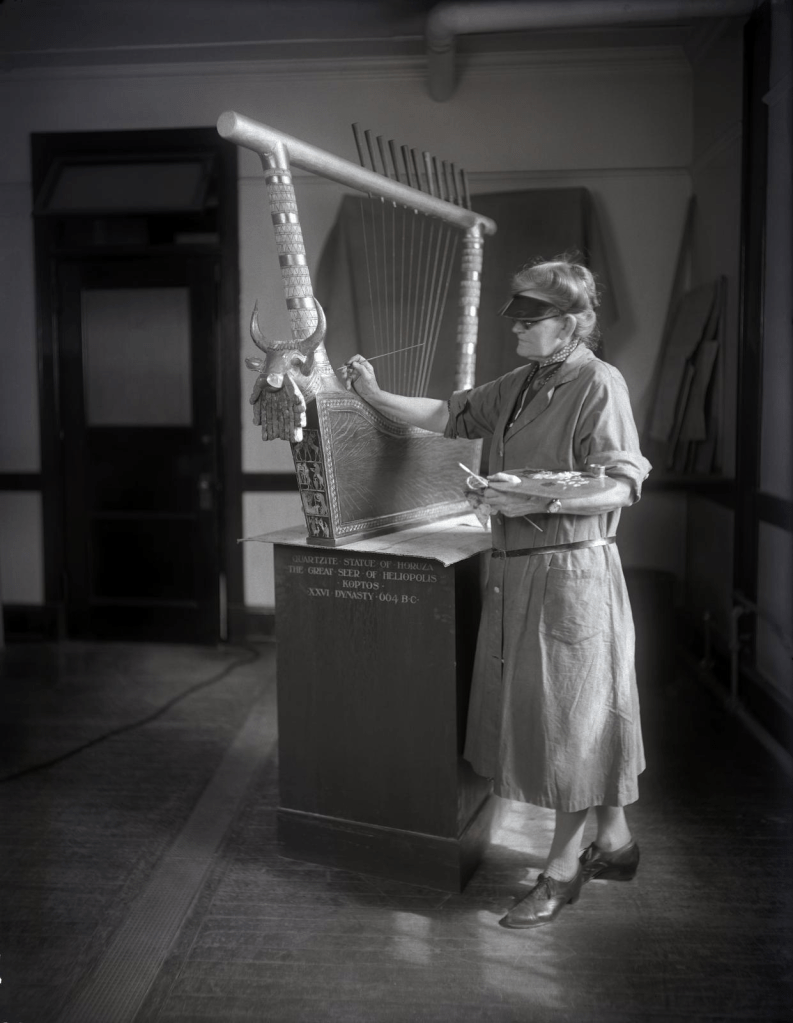

The Bull-Headed Lyre of Ur is one of the most iconic and well-preserved artifacts from ancient Mesopotamia. It is also one of the oldest string instruments ever discovered, dating back to around 2550-2450 BC. The lyre was unearthed in 1926 by British archaeologist Leonard Woolley, during his excavations of the Royal Cemetery at Ur in what is now southern Iraq.

Woolley and his team had been excavating the Royal Cemetery at Ur for several years when they came across tomb PG779 which was (they later decided) the burial place of Queen Puabi, a Sumerian queen who lived during the Early Dynastic III period. The tomb produced a treasure trove of grave goods, including gold jewelry, weapons, and pottery.

The lyre was found in a wooden coffin, along with the bodies of several attendants. Made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and shell, the lyre is decorated with intricate carvings and inlays, depicting a variety of scenes from Mesopotamian mythology and everyday life. The most striking feature of the lyre is its bull’s head, which is attached to the front of the soundbox.

Music was very important in ancient Mesopotamian civilization and was played during a variety of occasions, including religious festivals, royal banquets, and military campaigns. It was also used to accompany poetry, dance, and storytelling. For my story, I envisioned its use in private homes as well, even if occupants couldn’t afford anything as luxurious as the Bull-headed Lyre from Ur.

What would life have been like for the person who played such an exquisite instrument? Particularly for one who played in the court of a queen? To make my story work, I moved the lyre from its actual, historic era forward a couple hundred years to the reign of Sargon of Akkad, placing it in the Ekishnugal Temple in Ur where Sargon’s own daughter, Enheduanna, served as En, or high priestess, to the moon god Nanna. Enheduanna had her own court musicians, so I simply needed an individual to fit the role. From there, I simply told the story of how a girl with a passion for music ended up serving as music-giver for Enheduanna, the historic lyre her instrument of music-weaving.

I’d love for you to discover the inspiration of these pieces of art for yourself. Look for Masterworks on Amazon, available now.

About Stephanie Churchill

Being first and foremost a lover of history, Stephanie’s writing draws on her knowledge of history even while set in purely fictional places existing only in her imagination. Filled with action and romance, loyalty and betrayal, her writing takes on a cadence that is sometimes literary, sometimes genre fiction, relying on deeply drawn and complex characters while exploring the subtleties of imperfect people living in a gritty, sometimes dark world. Her unique blend of non-magical fantasy fiction inspired by real history ensures that her books are sure to please fans of historical fiction and epic fantasy literature alike.

After graduating college, she worked as an international trade and antitrust paralegal in Washington, D.C. and then in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was only at the suggestion of New York Times best-selling author, Sharon Kay Penman, that Stephanie began to write. She has since written three novels loosely inspired by the Wars of the Roses: The Scribe’s Daughter, The King’s Daughter, and The King’s Furies. Her first short story, Shades of Awakening, originally appeared in the Historical Writers Forum anthology, Hauntings. A Našû for Ilu, part of the Masterworks anthology, was published November 1, 2023.

Media:

Website: www.stephaniechurchillauthor.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.