The books I write are quasi-historical: they are set in a world with strong similarities to northern Europe after the decline of Rome. There are significant differences, but many of the events that shape it are based on real history. For my first two books, I was lucky – years of immersing myself in the Roman and post-Roman history of Britannia meant I had little actual research to do, except fact-checking. But the third took me out of the Britannia analogue – and into the library.

As I prepare to write the fifth full novel in the series, I am expanding into both a geography and a political history I know less about. So it’s time for more research, and in this month’s #authortoolboxbloghop, I look at how I do that.

When I say research, I mean major research, not the quick Google search for ‘how many public bread ovens were there in Rome’. (One for every 350 people, roughly, if you care.) Without giving too much away, the plot of Empire’s Heir, the next book, takes place mostly in Casil, my Rome analogue, and involves the politics of power as they rest in a high ranking, and therefore highly marriageable, young woman.

So, what major topics did I need to research this time?

Setting: Rome in the 4th C, which is the time in Rome’s history I chose to base my physical city on;

Character background: the education of an heiress to a country’s leadership in early-medieval Europe;

Politics: the politics and practicalities of marriage alliances.

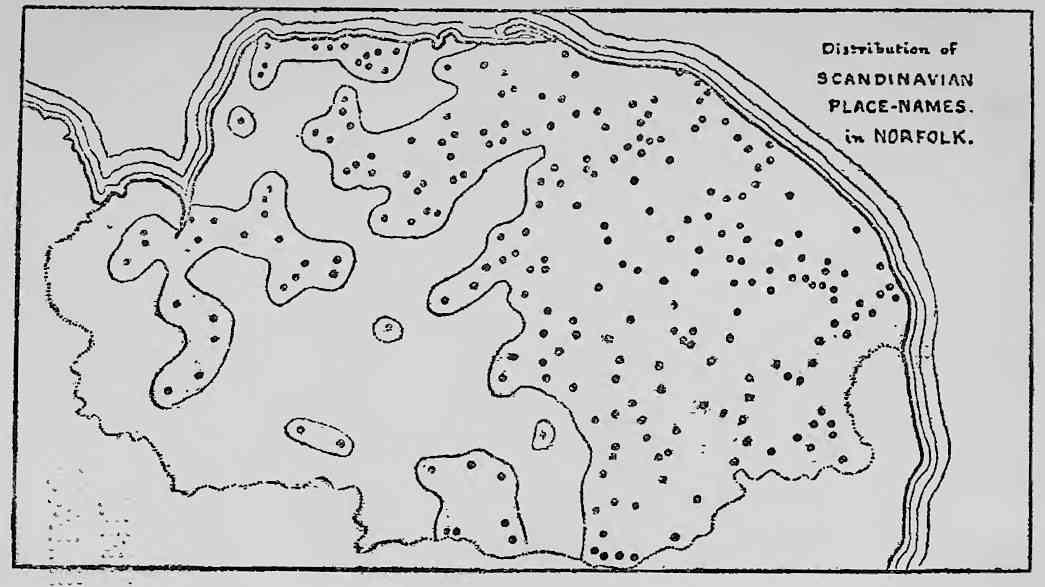

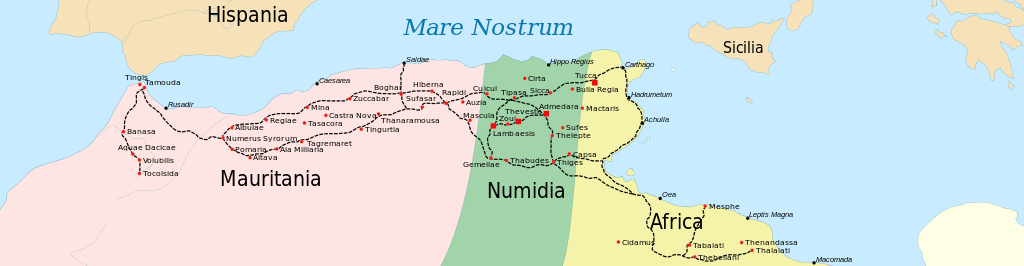

(In other books, it’s been battles, and ship construction, and travel times between Rome and Britannia, and Viking travel into continental Europe and Byzantium…whatever you’re writing about, you need to define what you’ll have to spend time researching.)

Let’s look at those topics one at a time.

Setting: Part of one of my earlier books takes place in Casil, so I’ve already done a fair bit of research. Three sources have been particularly useful

- Video reconstructions

- Ancient maps

- A research trip to Rome, with a private guide. (I realize this is a luxury out of the reach of many, but good guidebooks to ancient Rome could have been substituted, especially used in conjunction with the video reconstructions.)

What I have now are sources to refer to, and a fair understanding of the geography of Rome. Between watching the videos, taking an on-line course on ancient Rome, studying the maps and actually going to Rome, I’ve spent about two weeks – call it 80 hours – on this prior to beginning to write the book. I need to spend another 10 or so, I think, working with a map and the structures of buildings in conjunction with the plot of my story. Where are the stairs she’ll need to access? How long did it take to get from the Forum to the Pantheon on foot? What’s the easiest route for a character who is physically disabled to travel?

Character background: the education of an heiress to a country’s leadership in early-medieval Europe. I’m using a number of sources here, some on-line, more not: several new books on early-medieval women wait to be read. I did both a literature search, and asked some friends whose research area this is, to find the books to read. 40 hours here, for a solid understanding.

Politics: the politics and practicalities of marriage alliances. Again, more reading; some will be covered in the other books; some will be separate. I estimate 30 hours.

In total, I expect to spend 160 hours in major research prior to writing. Four forty-hour weeks. Some of it’s already done, so now perhaps I have 80 hours to do, or 2 full weeks. But I can’t devote 40 hours a week to research – while I work as a writer & editor full time, that includes all sorts of other writing (like this blog post), my editorial work, and promotion and marketing. Call it 6 weeks, then (providing I don’t find myself going down fascinating rabbit-holes of trivia.)

As fascinating as I find all this, I can’t focus on one subject for too long. So I will divide it up – a couple of partial days spent on the mapping and logistics (which I love, and can easily hyperfocus on); a couple of partial days spent on reading. The advantage, too, of doing it this way will be the cross-pollination of ideas that will occur – because while I have an overall plot outline, it will be the research that fills it out and provides details and plot twists I won’t necessarily have thought of. But it also means I won’t start the actual novel until September.

Sometimes I envy writers who get to make it all up!

If my books interest you, please consider signing up for my monthly newsletter, News from the Empire. It includes information about my characters and the history behind my world, short stories or vignettes, and pictures of my cat.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6d/45/6d450a9e-cd59-46eb-9000-206d05d3eee9/amazons.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.