By Helen Hollick

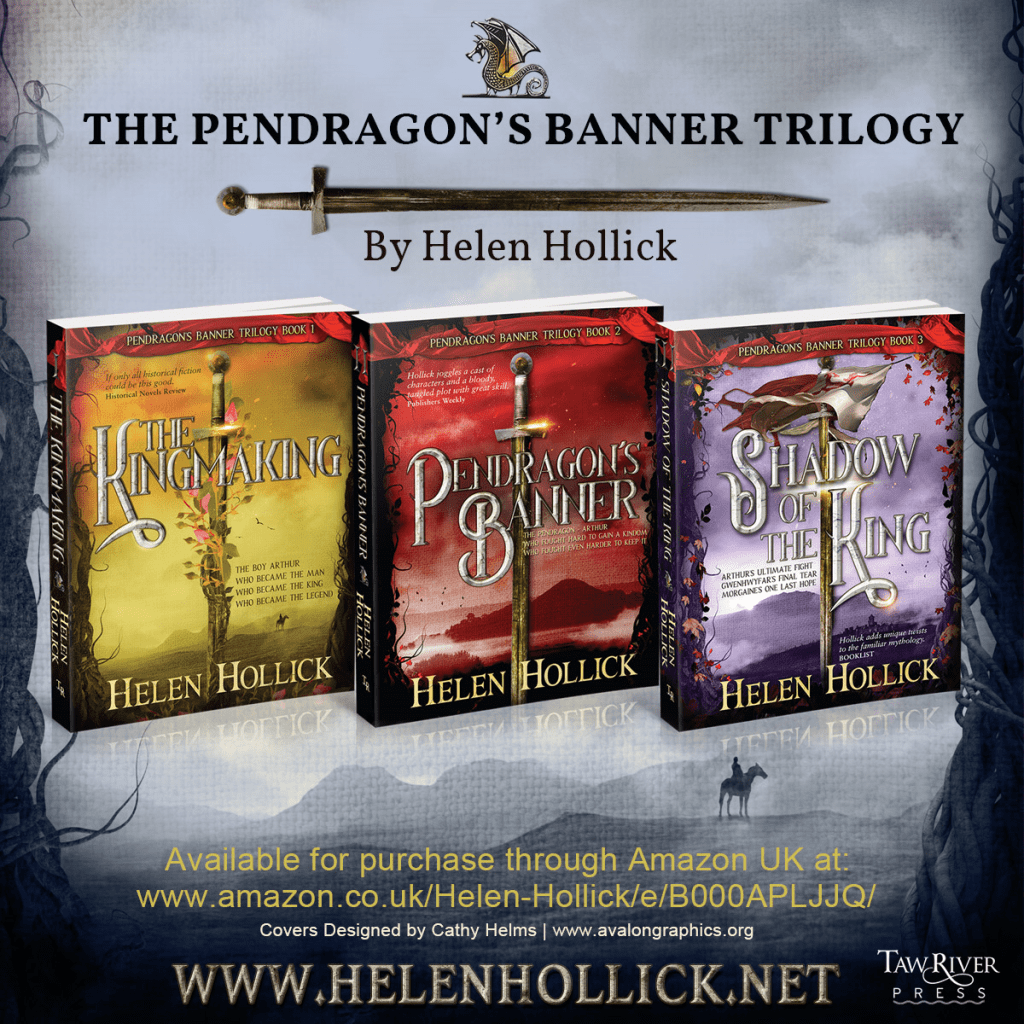

Pendragon’s Banner Celebration Tour April 2023

Thirty years ago in April 1993, one week after my 40th birthday, I was accepted by William Heinemann (now a part of Random House UK) for the publication of my Arthurian The Pendragon’s Banner Trilogy. It had taken me more than ten years to reach that stage of my dream to become a real writer – more than that if you count that I had been scribbling stories since the age of thirteen.

So why King Arthur? I had never liked the Medieval tales of knights in armour, the Holy Grail and courtly chivalry – I couldn’t stand Lancelot (what on earth did Guinevere see in him?) Why did Arthur go off on a religious quest for so many years? For me, none of those tales had the believability that writers today create in their novels of historical fiction. Arthur and the people of his court, if they existed, (and it’s a very big IF!) had no place in factual history after the Norman conquest of England. Those Medieval tales are merely entertaining stories, with the Holy Grail quest perceived, perhaps, to encourage men to join the Holy Crusades, and maybe the Arthur story mirrors the fact that Richard I spent many years away on his own ‘quest’ and very little time in his kingdom of England.

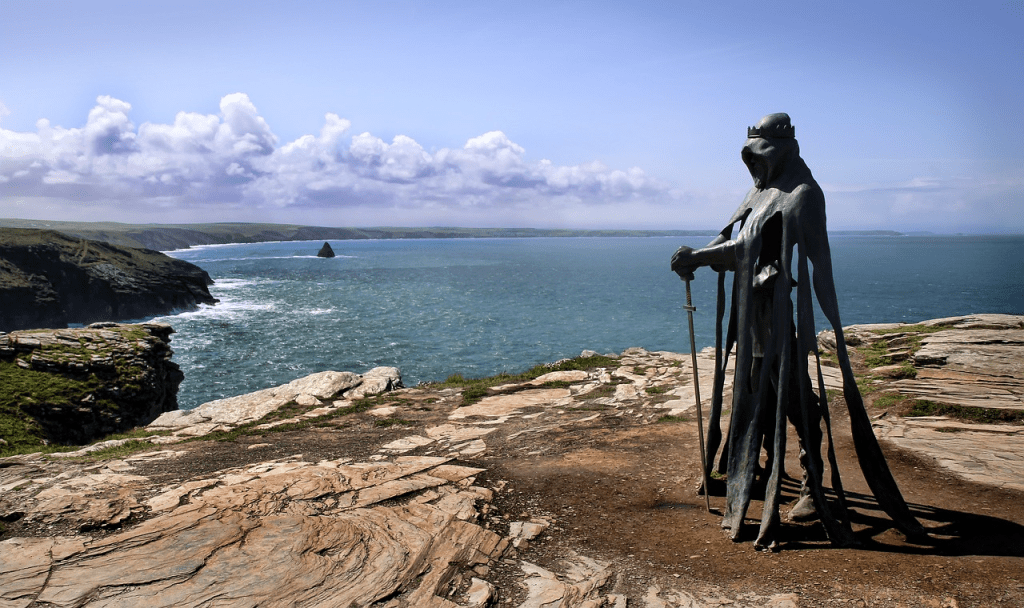

I was intrigued, therefore, when I discovered that there were earlier tales of Arthur, not only pre-Norman but pre-Anglo-Saxon. These were the Welsh legends, stories and poems of a warlord who fought against the incoming Germanic tribes. To place an Arthur figure during the upheaval and chaos of fifth-century Britain made sense. The period is not known as The Dark Ages for nothing, for written evidence, the whys and wherefores, are few and far between – we are, very much, ‘in the dark’ for the years around 430-550 AD.

So this is when I set my Arthurian tale, it is fiction – let’s face the fact, ‘Arthur’ as a king did not exist. (Sorry!) But even if he didn’t exist the earlier stories about him are wonderfully exciting.

I researched, as well as I could, the detail of post-Roman Britain (no internet back in the 1970s/’80s!) using archaeological evidence to add into the many, many imagined fictional bits, which include the Welsh tales and writing of clerics such as Nennius, who mentioned twelve battles that Arthur (supposedly) fought.

My character of Arthur, therefore, is a fifth-century warlord, passionate about fighting for his rightful place as King, and fighting as hard to keep it. As passionate, is the love of his life, Gwenhwyfar, who in my tale remains loyal to her lord, Arthur, despite their many ups and downs, hopes, fears, achievements and disappointments. Despite their laughter and tears.

I wrote my Arthur as a real man – warts an’ all. He is not the Christian king of the Medieval tales, he is a soldier, leader of the cavalry, the Artoriani, a man trying to sort the chaos Rome left behind, a man living in a world of upheaval, where Christianity is still in a state of embryonic flux, where pagan beliefs are still very much to the fore, and a world where Britain is changing, through battle and peaceful settlement, from a Province of Rome’s authority into the emerging kingdoms of Englalond – Anglo-Saxon England.

But maybe, just maybe, my story as told in the Pendragon’s Banner Trilogy is the base for how the enduring legend of King Arthur really happened…

© Helen Hollick

Helen’s new, self-published, editions with beautiful covers designed by Cathy Helms of www.avalongraphics.org are, alas, only available outside of USA and Canada, where the same books are published by Sourcebooks Inc. (The new covers were offered – free – to Sourcebooks, but the offer was declined.)

ABOUT THE KINGMAKING (Book 1)

The Boy Who became a Man:

Who became a King:

Who became a Legend… KING ARTHUR

There is no Merlin, no sword in the stone, and no Lancelot.

Instead, the man who became our most enduring hero.

All knew the oath of allegiance:

‘To you, lord, I give my sword and shield, my heart and soul. To you, my Lord Pendragon, I give my life, to command as you will.’

This is the tale of Arthur made flesh and bone. Of the shaping of the man who became the legendary king; a man with dreams, ambitions and human flaws.

A man, a warlord, who united the collapsing province of post-Roman Britain,

who held the heart of the love of his life, Gwenhwyfar – and who emerged as the most enduring hero of all time.

A different telling of the later Medieval tales.

This is the story of King Arthur as it might have really happened…

“Helen Hollick has it all! She tells a great story and writes consistently readable books” Bernard Cornwell

“If only all historical fiction could be this good.” Historical Novels Review

“… Juggles a large cast of characters and a bloody, tangled plot with great skill. ” Publishers Weekly

“Hollick’s writing is one of the best I’ve come across – her descriptions are so vivid it seems as if there’s a movie screen in front of you, playing out the scenes.” Passages To The Past

“Hollick adds her own unique twists and turns to the familiar mythology” Booklist

“Uniquely compelling… bound to have a lasting and resounding impact on Arthurian literature.” Books Magazine

The Kingmaking: Book One

Pendragon’s Banner: Book Two

Shadow of the King: Book Three

(contains scenes of an adult nature)

BUY THE BOOKS:

THE PENDRAGON’s BANNER TRILOGY

New Editions available worldwide except USA/Canada

https://mybook.to/KingArthurTrilogy

Available USA/Canada

US TRILOGY: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B074C38TXN

CANADA TRILOGY: https://www.amazon.ca/gp/product/B074C38TXN

ABOUT HELEN:

First accepted for traditional publication in 1993, Helen became a USA Today Bestseller with her historical novel, The Forever Queen (titled A Hollow Crown in the UK) with the sequel, Harold the King (US: I Am The Chosen King) being novels that explore the events that led to the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Her Pendragon’s Banner Trilogy is a fifth-century version of the Arthurian legend, and she writes a nautical adventure/fantasy series, The Sea Witch Voyages. She has also branched out into the quick read novella, ‘Cosy Mystery’ genre with her Jan Christopher Murder Mysteries, set in the 1970s, with the first in the series, A Mirror Murder incorporating her, often hilarious, memories of working as a library assistant.

Her non-fiction books are Pirates: Truth and Tale sand Life of A Smuggler. She lives with her family in an eighteenth-century farmhouse in North Devon and occasionally gets time to write…

Website: https://helenhollick.net

All Helen’s books are available on Amazon:

https://viewauthor.at/HelenHollick

Subscribe to Helen’s Newsletter: https://tinyletter.com/HelenHollick

Her Blog: https://ofhistoryandkings.blogspot.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/helen.hollick

Twitter: @HelenHollickhttps://twitter.com/HelenHollick

Follow Helen’s Celebration Tour https://www.helenhollick.net/

You must be logged in to post a comment.