While I’ll keep this website somewhat updated, for short stories, poetry, non-fiction, as well as more frequent updates, find me at

Category: Uncategorized

The Bull-Headed Lyre of Ur: A Masterwork of Ancient Mesopotamian Music

A Guest Post by Stephanie Churchill

The Masterworks Blog Tour

How many of us have wandered through an art gallery and daydreamed about a painting that catches our eye or an intriguing sculpture on the plinth? I definitely do. So the idea of coming up with a short story based on this premise didn’t require me to consider for long.

I had been researching Mesopotamia, particularly the foundation of the Akkadian Empire, when I learned about the discovery of the Bull-Headed Lyre of Ur. I have been trying for several years to write a work of fantasy using the Akkadians as an anchor for the setting of my fictitious world, but the final form of that book has been elusive. When I was invited to write a piece of short fiction, I realized that using this lyre would be a great way to use my research on the Akkadians even if my longer novel is proving difficult to finish.

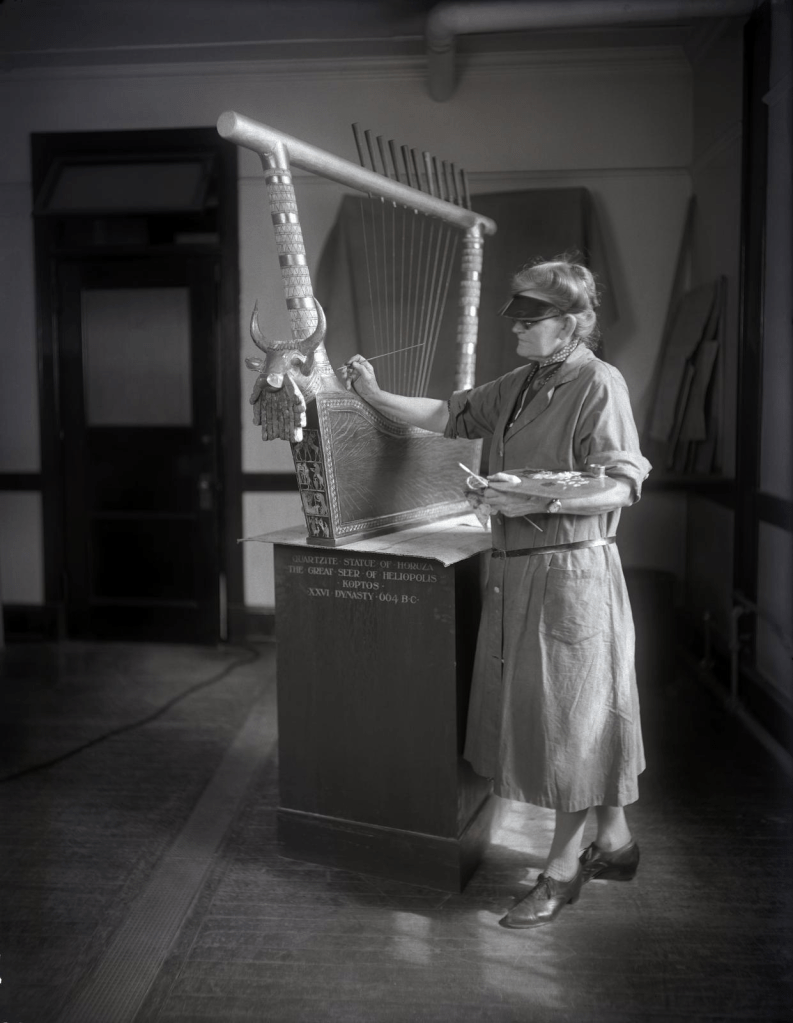

The Bull-Headed Lyre of Ur is one of the most iconic and well-preserved artifacts from ancient Mesopotamia. It is also one of the oldest string instruments ever discovered, dating back to around 2550-2450 BC. The lyre was unearthed in 1926 by British archaeologist Leonard Woolley, during his excavations of the Royal Cemetery at Ur in what is now southern Iraq.

Woolley and his team had been excavating the Royal Cemetery at Ur for several years when they came across tomb PG779 which was (they later decided) the burial place of Queen Puabi, a Sumerian queen who lived during the Early Dynastic III period. The tomb produced a treasure trove of grave goods, including gold jewelry, weapons, and pottery.

The lyre was found in a wooden coffin, along with the bodies of several attendants. Made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and shell, the lyre is decorated with intricate carvings and inlays, depicting a variety of scenes from Mesopotamian mythology and everyday life. The most striking feature of the lyre is its bull’s head, which is attached to the front of the soundbox.

Music was very important in ancient Mesopotamian civilization and was played during a variety of occasions, including religious festivals, royal banquets, and military campaigns. It was also used to accompany poetry, dance, and storytelling. For my story, I envisioned its use in private homes as well, even if occupants couldn’t afford anything as luxurious as the Bull-headed Lyre from Ur.

What would life have been like for the person who played such an exquisite instrument? Particularly for one who played in the court of a queen? To make my story work, I moved the lyre from its actual, historic era forward a couple hundred years to the reign of Sargon of Akkad, placing it in the Ekishnugal Temple in Ur where Sargon’s own daughter, Enheduanna, served as En, or high priestess, to the moon god Nanna. Enheduanna had her own court musicians, so I simply needed an individual to fit the role. From there, I simply told the story of how a girl with a passion for music ended up serving as music-giver for Enheduanna, the historic lyre her instrument of music-weaving.

I’d love for you to discover the inspiration of these pieces of art for yourself. Look for Masterworks on Amazon, available now.

About Stephanie Churchill

Being first and foremost a lover of history, Stephanie’s writing draws on her knowledge of history even while set in purely fictional places existing only in her imagination. Filled with action and romance, loyalty and betrayal, her writing takes on a cadence that is sometimes literary, sometimes genre fiction, relying on deeply drawn and complex characters while exploring the subtleties of imperfect people living in a gritty, sometimes dark world. Her unique blend of non-magical fantasy fiction inspired by real history ensures that her books are sure to please fans of historical fiction and epic fantasy literature alike.

After graduating college, she worked as an international trade and antitrust paralegal in Washington, D.C. and then in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was only at the suggestion of New York Times best-selling author, Sharon Kay Penman, that Stephanie began to write. She has since written three novels loosely inspired by the Wars of the Roses: The Scribe’s Daughter, The King’s Daughter, and The King’s Furies. Her first short story, Shades of Awakening, originally appeared in the Historical Writers Forum anthology, Hauntings. A Našû for Ilu, part of the Masterworks anthology, was published November 1, 2023.

Media:

Website: www.stephaniechurchillauthor.com

WRITING A SERIES by Helen Hollick

What could be easier? You have an idea for a new book, it doesn’t matter what genre – historical fiction, romance, fantasy, crime…The basic plot has popped into your mind and the characters come trooping into your life: the protagonists, the good guys, the bad guys. You start writing, the plot flows and the first draft is done. Then the editing, the cover design, the formatting. The excitement of publication day. Maybe an online launch and a book tour. And then you realise exactly what you have. The first part of a potentially cracking good series.

Now you wish you’d kept notes, details of what your characters were like – in looks and mannerisms. Eye colour, hair colour, tall, short, fat, thin? Their quirks and foibles. Maybe you should have delved into their backstories a bit more? Oh heck – I should have made a note of locations, of the little details. Believe me, unless you intentionally set out to write a series from the very beginning, all these possible continuity pitfalls suddenly appear like wasps at a summer picnic.

Readers notice, or at least, they will when your wonderful series takes off and the demand comes for ‘More!’

When I wrote Sea Witch, the first of my Captain Jesamiah Acorne nautical adventure voyages, I intended it to be a one-off tale, (not helped by my ex-agent who had no faith in it – hence the ‘ex’!) But readers loved it (and Jesamiah,) so I had to write another adventure for him, then a third… I’m in the process of starting the seventh full length yarn. And I wish I’d made more notes along the way.

Lesson learned, I keep notes for my Jan Christopher Cosy Mystery series (that’s coZy in US spelling). The location for the episodes set in the north-east London suburb of Chingford are not a problem as it’s where I used to live and work in the public library back in the 1970s. Apart from the roads where murders happen, all the streets and places are the real thing. (I’ve made the murder locations up, though, in case of any residents’ sensitivity.) The library itself, South Chingford, was an actual place. The building still exists but the local council closed it as a library several years ago (shame on them!) and it is now used as offices. I’ve quite enjoyed bringing the old place back to life; remembering all the goings-on during the thirteen years I worked there. The characters, however, are entirely made up – although several of Jan’s anecdotes are partially biographical.

I decided to deliberately alternate location settings between each book, primarily because I was torn between writing about Chingford as it was, and my present life here in glorious North Devon … so episode 2 (A Mystery of Murder) saw Jan and boyfriend Detective Sergeant Lawrence Walker visiting his parents for Christmas 1971, who live in the fictional village of Chappletawton. Based on my village – but not quite the same.

All well and good, but by the time I got to episode 4 –which again sees a return to Devon, I had to ensure I had the right place names, the right village residents … was Bess, the dog, a black or golden labrador? What had I called the neighbouring farmer? And even more important, which characters leant themselves to becoming possible murder suspects and which ones were reliable witnesses?

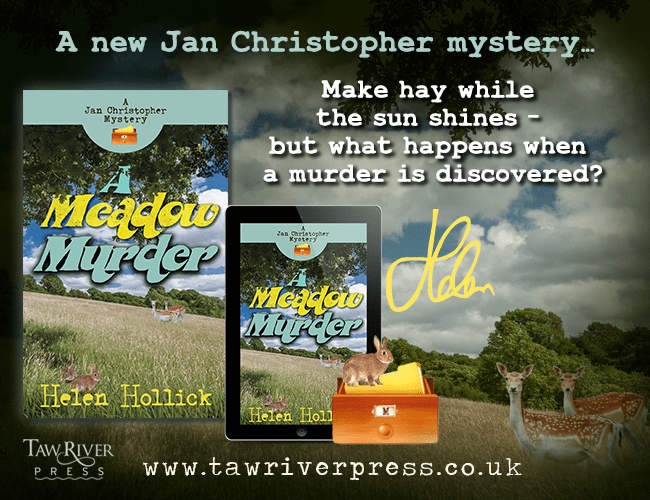

I think I’ve managed to tie everything together in A Meadow Murder, introducing new characters, revisiting previous friends, and remembering to make notes for the next planned instalments…

ABOUT A MEADOW MURDER

A Meadow Murder is the fourth tale in the Jan Christopher cosy murder mystery series, the first three being A Mirror Murder, A Mystery of Murder and A Mistake of Murder… see what I’ve done there? Yes, I’ve created a proper puzzle for myself because now every tale in the series will have to follow the same title pattern of ‘A M-something- of Murder’ (Suggestions welcome!)

Based on working as a library assistant during the 1970s for almost thirteen years, the mysteries alternate between the location of Chingford, north-east London, where the real library I worked in used to be, (the building is still there, but is, alas, now offices) and my own North Devon village, but slightly fictionized. Chappletawton, for instance, is much larger than my rural community and has far more quirky characters, (and we haven’t had any real murders!)

The main characters, however, remain the same: Jan Christopher is the niece, and ward, of Detective Chief Inspector Toby Christopher and his wife, her Aunt Madge. In A Mirror Murder, Jan (short for January, a name she hates) meets her uncle’s new driver, Detective Constable Lawrence Walker. Naturally, it is love at first sight … but will an investigation into a murder affect their budding romance?

We find out as the series continues: Episode Two takes the young couple to spend Christmas at Laurie’s parents’ old farmhouse in Devon, while Episode Three sees us back at work at the library in the north-east London suburb of Chingford. We yet again travel to Devon for Episode Four – A Meadow Murder. And no spoilers, but the title is a little bit of a giveaway!

I had the idea for A Meadow Murder during the summer of 2022, while watching our top meadow being cut for hay. The cover photograph for A Meadow Murder is my field – a real Devonshire hay meadow, and the scenes in the story about cutting, turning and baling the hay are based on how we really do it. (Even down to the detail of the red Massey Ferguson tractor.)

In fact, I’m very glad that we cut and brought in our 480 bales of hay this year back in June when it really was a case of ‘make hay while the sun shone.’

I am relieved to say, however, that we didn’t find a body…

“As delicious as a Devon Cream Tea!” author Elizabeth St John

“Every sentence pulls you back into the early 1970s… The Darling Buds of May, only not Kent, but Devon. The countryside itself is a character and Hollick imbues it with plenty of emotion” author Alison Morton

*

Make hay while the sun shines? But what happens when a murder is discovered, and country life is disrupted?

Summer 1972. Young library assistant Jan Christopher and her fiancé, DS Lawrence Walker, are on holiday in North Devon. There are country walks and a day at the races to enjoy, along with Sunday lunch at the village pub, and the hay to help bring in for the neighbouring farmer.

But when a body is found the holiday plans are to change into an investigation of murder, hampered by a resting actor, a woman convinced she’s met a leprechaun and a scarecrow on walkabout…

Buy Links – Paperback or e-book, including Kindle Unlimited

Amazon Universal Link: this link should take you direct to your own local Amazon online store https://mybook.to/AMeadowMurder

Also available worldwide, or order from any reliable bookstore

All Helen’s books are available on Amazon: https://viewauthor.at/HelenHollick

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: HELEN HOLLICK

First accepted for traditional publication in 1993, Helen became a USA Today Bestseller with her historical novel, The Forever Queen (titled A Hollow Crown in the UK) with the sequel, Harold the King (US: I Am The Chosen King) being novels that explore the events that led to the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Her Pendragon’s Banner Trilogy is a fifth-century version of the Arthurian legend, and she writes a nautical adventure/supernatural series, The Sea Witch Voyages. She has also branched out into the quick read novella, ‘Cosy Mystery’ genre with her Jan Christopher Murder Mysteries, set in the 1970s, with the first in the series, A Mirror Murder incorporating her, often hilarious, memories of working as a library assistant.

Her non-fiction books are Pirates: Truth and Tales and Life of A Smuggler.

She lives with her husband and daughter in an eighteenth-century farmhouse in North Devon, enjoys hosting author guests on her own blog ‘Let Us Talk Of Many Things’ and occasionally gets time to write…

Website: https://helenhollick.net

Subscribe to her Newsletter: https://tinyletter.com/HelenHollick

Main Blog: https://ofhistoryandkings.blogspot.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/helen.hollick

Twitter: @HelenHollick https://twitter.com/HelenHollick

The Real Rheged: A Guest Post from Maria Johnson

Maria’s newest book, The Reckoning of Rheged, is newly out, so I invited her to talk about her books, set in northern Britain in the early-medieval period.

Hi all, today on this guest blog post (thanks again Marian!) I thought I’d talk about the real history behind the kingdom of Rheged.

The series began in 2018 with my debut novel, The Boy from the Snow. It’s the story of my main character Daniel, a warrior who must choose who his friends and foes really are when he discovers a truth about his past. The sequel The Veiled Wolf was published in 2019.

The Reckoning of Rheged, the third novel in the series, was just published last week, so I thought it would be an apt time to revisit the historical backdrop.

The Real Rheged – the setting

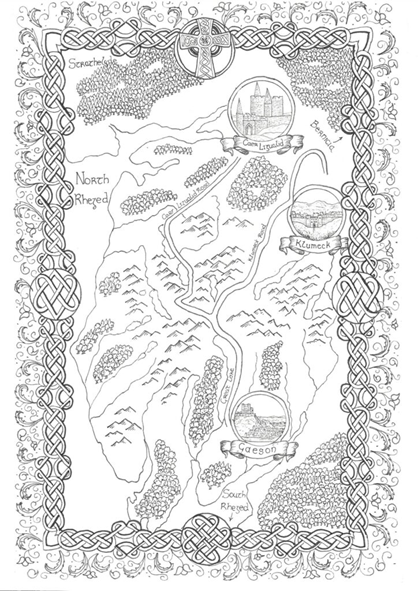

Allow me to share a bit more about the historical world of Rheged. This map of North Rheged was designed by my friend Beth Baguely.

As you’ll see on the map, the Kingdom of Rheged was a real Brittonic Kingdom that spanned much of Cumbria, Lancashire and into Cheshire, stretching as far east as the Pennines. The capital city of the kingdom was Caer Ligualid, based in modern day Carlisle. King Urien, Rheged’s most famous king who ruled over the entire kingdom, really did exist, as did his son Prince Owain.

While the kingdom of North Rheged and its city Caer Ligualid really existed, the smaller kingdoms of Gaeson and Klumeck are purely fictional. I set Gaeson at Gummer’s How, a hill near Lake Windermere at the heart of the Lake District. The kingdom of Klumeck is much further to the east, at the border to the kingdom of Bernicia. I imagine it would be based in the Pennines, perhaps Cross Fell.

The Real Rheged – the History

When writing this history of kings and war and Daniel going on a quest or two, it really can feel like a fantasy, especially with the main characters being fictional. However, I have also really tried to intertwine the fictional story with the historical, from large-scale battles recorded, to small little details like what my characters would have eaten and worn during this time.

One of my most enjoyable aspects of writing historical fiction is to have Daniel meet the real historical figures of Rheged. Another one of the most famous characters Daniel encounters is King Urien’s bard, Taliesin. Taliesin was one of North Rheged’s most famous poets, whose work is still read today. In fact, his writings are a substantial part of Welsh classic/historical literature, as well as recording much of the primary sources that we have for the period.

Not to spoil things too much, but the antagonist in the third novel is also based on a real historical figure who opposed Rheged’s kings. A lot of my research was done online. The early writings of Taliesin, as well as the monk Bede, have been crucial to research. I also have a one or two historical reference books I go back to again and again that cover the era as a whole.

After deciding on the era for the story, it took a lot of research to understand the way people would have lived. Details like what they would have eaten, how they would have dressed and what names people would have had were frequent Google searches, as well as the religious scene/worldview of the time. The worldview of Celtic Rheged is predominantly Christian, due to the Roman influence from when they occupied Britain a couple of centuries before.

The Real Rheged – the worldview

As a Christian myself, being able to have my faith naturally bleed into my writing was another reason for picking the era I did. Although the book is not specifically Christian fiction, Daniel talks openly about his faith and I do pick up on some Christian themes. This is one of the reasons my MC is called Daniel, as well as another few side characters (Sarah, John, Joshua, Rachel, Ruth). I tried to have a few names that were biblical in origin, due to the Roman influence. The vast majority of names, though, are Brittonic Celtic.

Whilst I’m by no means a historical expert on the era, I’m hoping that through telling Daniel’s story – and now Imogen’s – it sheds some light (no pun intended) onto the Dark Ages. Hopefully it will spark imagination of what this world was really like. Ultimately, I hope you enjoy reading about Rheged as much as I have done writing about it.

If you’re interested in checking out my historical fiction, all three of my books are available on Amazon, as either Ebook or paperback. They’re also in KU.

Why not sign up to my newsletter? You’ll get a free copy of an Edwardian historical mystery romance The Oak Tree Calls, exclusive to subscribers.

Thanks for having me!

Maria

Hiatus

I’ve been mostly absent from social media, blogging, promoting my books, and generally any on-line presence for most of January. Since the 9th of the month, I’ve been in England, getting here just in time to see and have lucid, intelligent conversations with a very elderly cousin before she died four days later, and since then, dealing with all the responsibilities of an executor. The death to register, the lawyers to meet, the funeral to arrange, the house and contents to be valued, banks and utilities to be informed – anyone who’s been through this knows there is a lot to do. I’ll be here a few weeks yet: the house will go up for sale, the valuable contents will be auctioned, with some items needing specialist sales (more research). There’s a piano to be shipped. An energy audit required on the house. The list sometimes looks endless.

In between, of course, I do the grocery shopping and take carloads of things to charity shops (both involving an hour’s round trip from the tiny north Norfolk village my cousin called home), and call people to take away the stairlift and the mobility scooter…and once in a while I take a couple of hours off and go birding, for sanity.

And somewhere, in this last week, I stopped agonizing over the book that isn’t being written, or the retweets that aren’t happening, or the books I’m not reviewing, or the promotions I’m not posting. For two major reasons: one practical, one—philosophical, perhaps?

Practically, there aren’t enough hours in the day; at two months short of 65, I don’t have the energy I once did. Just getting through what needs to be done, taking time for at least a short walk, and preparing three meals a day, simple as they are (and cleaning up) is all I’m going to do.

I’m not 40-something now, even if my mind thinks I am.

Philosophically, there’s also the processing of loss, of saying goodbye. I won’t say I’m grieving, exactly: my cousin was nearly 102, had lived a marvelous life, and was ready to go. I’ll miss her, though: miss her stories of Oxford in the war years and of her first teaching job in a remote Cumberland village; miss her erudite and incisive opinions of literature classic and modern (don’t get an MFA, she told me, everyone who does writes in the same way). I’ll miss her ability to quote long passages of the metaphysical poets and Macauley’s Lays of Ancient Rome. She once spent some considerable time working out if my Latin-based conlanguage has proper grammar. (It doesn’t.) She liked my books: they made her think, she said. She left me, specifically, her library.

Sorting through the remnants and memories of a life takes time, and it takes attention. I was entrusted with this task because she said I’d know what was important. Honouring that takes time and attention and energy, too. So Empire’s Passing will wait, and I’ll lose followers on social media and my other books sales will drop. But I will have kept a promise, and that matters more.

And someday–maybe–I’ll be back.

Cloud Cover, by Jeffrey Sotto: A Review.

Cloud Cover balances the specific with the universal with ease and elegance, a tribute to the author Jeffrey Sotto’s skill. The protagonist of the book is a 30-something, gay, Filipino man living in Toronto, which could have made some readers feel the story is beyond their experience. The character of Tony is drawn with precision: he is not an everyman. He is himself, flawed and damaged, from external and internal causes, and relatable to anyone who has dealt with personal loss or rejection.

This isn’t to say Cloud Cover is an easy read. Tony’s bulimia is described in some detail, and he is likely to exasperate the reader as much as he does his friends. On the other hand, parts of Cloud Cover are laugh-out-loud funny, a nice balancing act from the author.

I found myself really caring what happened to Tony, both in his new, hopeful relationship and in his work towards healing. Sotto moves Tony past his ‘identity’ to find commonalities of the human experience: the devastation of grief; the joy of true acceptance; the pressure to conform. Nor is Tony’s life always bleak: he finds contentment, sometimes happiness, in parts of his life; a compromise, but one that will be well understood by many readers.

Sotto develops the story with compassion tempered by a clear look at the realities of a mental health disorder. Ultimately Cloud Cover is a hopeful book, but in a realistic way. There is no easy fix, no person but Tony who can turn his life onto a track less damaging, and not without significant, difficult work. But he can, by the end, see at least a hint of the sun behind the clouds, and the reader is left believing in a better future for Tony. Strongly recommended for readers of contemporary novels with believable, realistic protagonists.

Reviewed for Coffee and Thorn Tours.

- Purchase link: https://mybook.to/CloudCover_Amazon

- Goodreads link: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/56811092-cloud-cover

Jeffrey Sotto graduated from The University of Toronto, majoring in Film Studies and English Literature. He was the screenwriter and script consultant of the Canadian short films The Tragedy of Henry J. Bellini (2010) and Sara and Jim (2009), respectively.

Cloud Cover, his first novel, published in 2019, won a Best Indie Book Award (BIBA) for LGBTQ Fiction, an Independent Publisher Bronze Medal Book Award (IPPY), and a Literary Titan Book Award. It also briefly topped the Amazon bestseller list in LGBTQ fiction upon release. He published his second novel, The Moonballers: A Novel about The Invasion of a LGBTQ2+ Tennis League … by Straight People (GAY GASP!) in Spring 2022.

Jeffrey is also an advocate for mental health and eating disorder awareness and recovery, having shared his story on CBC Radio, Global News, and Sheena’s Place. He is currently a peer mentor at Eating Disorders Nova Scotia (EDNS). He will be contributing to the anthology Queering Nutrition and Dietetics: LGBTQ+ Reflections on Food Through Art, to be released in December 2022. Finally, in 2023, he will be appearing in the docuseries Wicked Bodies by Truefaux Films, which focuses on fostering positive culturally competent engagement in treatment and support centres, universities, and non-profit programs working with LGBTQ+ groups with disordered eating and body dysmorphia.

He is a self-proclaimed “cubicle dreamer,” tennis addict, and compulsive social media duckfacer.

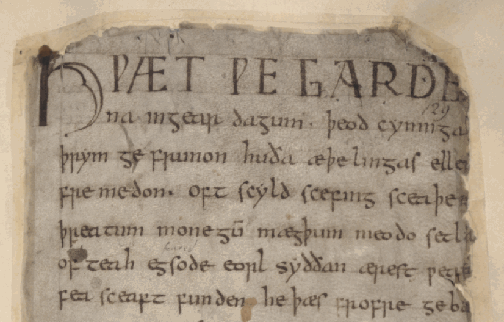

Writing Beowulf

“I need a challenge,” I told my husband the other day. I’ve not long finished my newest book, I’m not ready to start the next one, and I was rather at loose ends. Until I remembered a project I’d half-considered earlier: an adaptation of Beowulf.

In Empire’s Heir, my sixth book, the character Sorley hears a tale new to him, and, because he is a bard with all the responsibility that title carries: historian, poet, cultural custodian– he puts the tale into verse and music. The conceit is that the poem he writes is Beowulf – but as no one knows who wrote it, why not Sorley?

Half an hour later, Sorley had finished singing about Hrothgar and heroes and monsters, and I could stand without too much pain.

“That is not a danta* for children,” I…

View original post 153 more words

HistFic Outside the Box

Creative and unconventional doesn’t always describe historical fiction and its subgenres, but today (and until Nov 30) five authors are offering you exactly that.

Click HERE to see the books by:

Bryn Hammond, stories derived both closely and imaginatively from The Secret History of the Mongols.

Julie Bozza, with books set from Rome in the 19th century to the ‘wild west’, with historical characters seen through a different light.

Elles Lohuis, whose stories transport you to 13th century Tibet.

Laury Silvers, offering detective stories set in 10th century Baghdad, exploring not only solving the crime, but the paths of Sufi practitioners.

And mine, a reimagining of what a world that looks a lot like Europe after the decline of Rome might have been.

Great storytelling combined with diverse representations of places, times and peoples – take a look!

Empress & Soldier

A boy of the night-time streets; a girl of libraries and learning.

Druisius, the son of a merchant, is sixteen when an order from his father that he can neither forgive nor forget drives him from home and into the danger and intrigue of the military.

Eudekia, a scholar’s daughter, educated and dutiful, is not meant to be a prince’s bride. In a empire at war, and in a city beset by famine and unrest, she must prove herself worthy of its throne.

A decade after a first, brief meeting, their lives intersect again. When a delegation arrives from the lost West, asking Eudekia for sanctuary for a princess and support for a desperate war, Druisius is assigned to guard them. In the span of a few weeks, a young captain will capture the hearts of both Empress and soldier in very different ways, offering a future neither could have foreseen.

A stand-alone novel that can also serve as a second entry point into the Empire series. No previous knowledge of my fictional world is needed.

Electronic ARCs available after November 15, 2022. Email request to arboretumpress (at) gmail.com

Writing for Effect: A dialogue with Bryn Hammond

This is the first in a blog series, the purpose of which is not only to spotlight an author’s work, but, in a dialogue between myself and the author, to illustrate the variety of ways the techniques of writing can be used, and how styles differ. My first guest is Bryn Hammond, author of Amgalant, historical fiction based on the Secret History of the Mongols, which is is the oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolian language. It was written for the Mongol royal family some time after the 1227 death of Tchingis Khan (Temujin). Bryn has chosen to discuss how she used poetic speech, homely metaphor, and lively conversation in her work.

Bryn

This is going to be about Amgalant, my main work – my life’s work, though I potter with other things.

I call my historical fiction a ‘close reading’ of the Secret History of the Mongols. More than a source, the Secret History is my original, and I want to imitate its features – not merely its content. Early on, I confronted the fact that I had one major difference from most historical fiction: that I am text-based, text-to-text, not trying to re-create history as such but to give a version of a story already told. In search of a model or template, I looked to T.H. White and Malory. White’s Once and Future King riffs on Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, quotes Malory, talks to him and about him. That was me and my text. I was after a deep fidelity, and yet room to be myself – as T.H. White does not shy from idiosyncrasy of style or interpretations that are meaningful to him. My aims often felt like a contradiction, but as my Temujin says once, ‘Contradictions, when they work, generate much heat and light, or else they blow up in your face.’

Topic: poetic speech

In my first excerpt, young Temujin composes a message to his anda – a friend with whom he has exchanged blood, where resides the soul. His anda too has suffered at the hands of the king who has stolen Temujin’s wife. This is Temujin’s request for Jamuqa to join him in a war of rescue.

Simplest leaves least to go wrong, he thought, and he stitched together a few simple verses. Verses, for formal wear. And when underway he found that verses gave him a truer language, truer to his emotion, that was only flagrant in daily felts and furs.

They have cut the liver from my side.

How our fates, my anda, coincide.

Can we right the wrong?

We feel each other’s injury:

Your wound bleeds my blood and mine bleeds yours.

My other self, can I avenge you?

Can you comfort me?

It was his first draft, but he didn’t fiddle.

I feel strongly that I have to use as much poetic speech as does the Secret History, or else I belie the rich oral culture of the Mongols as well as the techniques of my original. The Secret History itself gives much weight and space to the spoken word. I am dialogue-heavy, but only in equivalence to my original. The Secret History marks significance by turning a speech into poetry, but it also reports people’s own poetic speech. People use this particularly when they need to be ceremonious, or courteous, or emphatic, or heartfelt.

Now, Temujin grows into a great ability with words. Here he is young and gauche and not used to formal communications. It is his first go at a message in verse. I had to make him heartfelt, I had to make him sound first-drafty, spontaneous, yet suggest he has a knack for this.

I took the opportunity to explain, through his experience, the value of talking in verse from time to time. Of course, the challenge is not to be off-putting to a readership who doesn’t burst out into verse, who might tend to see verse as stilted, as the opposite of spontaneous and heartfelt. I have to convince readers that the Mongols, in a culture of oral poetry, could slip into poetic speech with facility and no loss of genuine feeling.

Marian

“No loss of genuine feeling.” – or maybe a way to express deeper feelings, or perhaps more subtle ones? The use of ‘flagrant’ in verses gave him a truer language, truer to his emotion, that was only flagrant in daily felts and furs is an interesting choice – I think of ‘flagrant’ as meaning ‘blatant’, or even ‘over-the-top’, so I read this as an indication that verse allows him to convey a more nuanced, truer emotion.

The use of avenge/comfort in juxtaposition – I think Western perceptions of Mongol culture (as a warrior society) would expect ‘avenge’ but not ‘comfort’. The cognitive dissonance for the Western reader here speaks to our own preconceptions, but what does it reveal about Mongol society?

My last comment on this section is that the use of verse here in formal (courteous, ceremonial) context is reminiscent of Shakespeare, where nobles speak in verse but commoners do not. Did you consider that at all?

Bryn

With ‘flagrant’ I wanted to suggest an extravagance of emotion, that might have seemed too much to talk about. Verse gives him permission to feel as much as he feels, and say so. ‘Comfort’ I chose with great care, aware that it subtly undercuts preconceptions about the Mongols. I can say the same of hundreds of other choices I made.

There’s a word, ‘hachi’, important to the story from the start, because a khan before Tchingis, captured and tortured by China, sends a message back to his people in which he asks for ‘hachi’ – a message Tchingis cites as motivation when he strikes at China over thirty years later. If you’ve read a history on the Mongols you’ve probably seen ‘give me my hachi’ translated simply as ‘avenge me’. Now, my interest in revenge as a motive, whether I’m reading or writing, hovers around zero. So I’m going to look closely at that word, and I’m going to give you more shades to its meaning. I have Temujin’s grandfather think about the word when he hears the captured khan’s message:

Hachi means that which is owed, or felt due. It can mean an act of humanity. It can mean vengeance. It meant justice.

The word occurs in the Secret History for both gratitude and revenge. That’s nothing if not juxtaposition. ‘Hachi’ became one of my most beloved words to use – one I leave untranslated, because my reader has grown familiar with its cluster of meanings.

There is a strong tendency to translate things, understand things, believe things as per our preconceptions. When I began to write about the 13th-century Mongols, back in 2003, I had to dismantle the preconceptions in my own head. That wasn’t a short or easy process – it took real vigilance, self-examination, again and again stepping back to question.

On Shakespeare – I am a Shakespeare-head. I am certain he helped teach me how one talks in verse, or how verse can be a cadence in more ordinary speech, when the culture is steeped in it. The noble/commoner split doesn’t map onto the Mongol situation, at least in my telling (everything about the Mongols is contested, everything).

Topic: homely metaphor

My next excerpt is Temujin as Tchingis Khan, a king, fifteen years later. He has been caught listening to what his companions are saying about him.

Laughingly he called across to him, “Ile Ahai, you have your hare by the ears. I listen to learn, to learn what you make of me, for you are one of my principal makers. You make very much, but I shan’t be cowed, neither embarrassed. For my task is a joint labour and whereas Temujin is me, Tchingis is us. Mine is the sack, yours is the milk poured in; Tchingis is stood by the door with the churn in his neck and together we try to beat him a thousand times a day, and whenever we step in or out we lend a hand.”

To help write Temujin’s turn for homely metaphor, I admit I thought of Jesus’ parables in the Bible, that use a humble subject matter. Temujin’s style as a king is humble and common, but a gift for speech is among his greatest assets. So this is one of Temujin’s little parables, based on a homely subject: the process of churning milk into the fermented drink ayrag. It is spoken to his inner circle, and involves them in the Tchingis project, in his kingship.

Metaphor is much used in speech acts recorded by the Secret History – and other Mongol histories. Sometimes, at a critical moment, people have expressed themselves by a metaphor whose context is lost to us, and we can’t make sense of what they say. My challenge is to keep my English-language readers familiar enough with Mongol daily life that I can use those metaphors drawn from humble things, without the clunk of an explanation in (figurative) brackets. To work, this piece of speech has to have the casual references to ayrag-making and -drinking through the few hundred pages before it.

Marian

The concept of the separation of Temujin from Tchingis – the individual vs. the role really struck me (perhaps because I am writing a character in a similar situation.) The ‘homely metaphor’ works really well here to delineate this separation of person from position, and using the Mongol analogy brings it into its context beautifully. Which came first, the references to ayrag-making and -drinking in the previous pages, or the metaphor?

The lost metaphors: I couldn’t help but be reminded of the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Darnok, where Picard is trapped on a planet with an alien captain who speaks a metaphorical language (from his own culture) incompatible with the universal translator. I don’t know if that means anything to you, but while (of course) it was easily solved, there are other examples in the Scandinavian sagas and perhaps even in Old English where we don’t understand the metaphors, concepts lost to time and change. It also brings to mind Robert MacFarlane’s book The Lost Words, which came about because of the loss of words related to nature in the 2007 edition of The Oxford Junior Dictionary. How much, do you think, are the lost metaphors due to cultural change separate from the evolution of language?

Bryn

Which came first? Daily life, always. Then it is there when you need it – waiting to be picked up in a metaphor.

I loved that Star Trek episode – particularly because those metaphors were drawn from a body of epic story. And then Picard recites from Gilgamesh to the alien! – my heart.

So yes, I think a lot of the loss is down to lost story, lost anecdotes. Most unfortunately, the only survivals of the oral story-world that Temujin lived in, pre-writing, are snippets extracted for use in other contexts. We know there was a wealth because of the Secret History’s ease of reference, as well as by analogy to the vast and wondrous world of Turkic epic, that began to be recorded from medieval times on because of its proximity to writing cultures.

Topic: lively conversation

Back to young Temujin for my third excerpt. He faces a circle of experienced companions-in-arms, who laugh – or try not to laugh – at Temujin’s naivety over the size of armies mentioned by his patron the khan of Hirai.

Grey-tailed Jungso of Noyojin started to effervesce silently and couldn’t stop. Others, two or three of them, told him, “Jungso. Jungso, don’t be uncouth.”

“I’m not,” he effervesced. Then he claimed, “I’m laughing at the khan of Hirai.”

“Fair enough, too,” declared Jirqoan of Oronar. “It helps when people are precise in military matters. Tumens,” he addressed to Temujin, “you can bet your bottom goat, is here imprecisely used.”

Temujin turned student-like to him. “A tumen doesn’t mean ten thousand?”

Bisugat, next to Jirqoan, answered. “In a fat year, like a cheese. Cheeses shrink in a lean year, but we still call them a cheese.”

It is an often-acknowledged truth that the real hero of the Secret History of the Mongols isn’t Tchingis Khan but his companions. I do a lot of group conversations to convey the input of the group. This means I have cast members who have one line, but I still want them to feel alive, like individuals.

One reason I chose the Secret History of the Mongols is its wonderful exchanges of speech. That suited the writer that I am. In historical fiction, the danger is that speech becomes stiff and stilted, in part because our slang isn’t theirs, in part because we often hear them through paperwork and not everyday speech at all.

Marian

The group conversations convey the richness of the oral culture and the importance of individuals within it.

I loved ‘bet your bottom goat’ because I as an English-speaker of a certain age and time expected ‘bet your bottom dollar’ and that it wasn’t that familiar phrase reminded me very sharply that this was a different time/place/culture. Was that your intent?

The flexibility of the measure of a tumen is superb, so easily understood. Is this your invention, or something shown in the Secret History of the Mongols?

Bryn

I do like to merge English-language slang with Mongol slang. This one was an easy example. I use whatever Mongol slang and figures of speech I can convey sense in, but where I need to amalgamate them with English idiom for explanatory value, I don’t scruple to do that.

Sometimes there’s a clash that’s fun to work with. Milk is a substance for infinite idioms in Mongol, which often come straight across in English. But if Westerners hear ‘he has milk in his veins’, they might well assume that’s an insult. In Mongol idiom, milk is pretty much always positive, and this isn’t said negatively, although it does tie in nicely with the English – and Shakespearean – ‘milk of human kindness’.

Tumens: This explainer was me.

You can find more information on Bryn and her books at

or purchase her books here

https://payhip.com/b/2ERGv or https://books2read.com/ap/xK6AY8/Bryn-Hammond

Would you like to be part of this series? Authors published or unpublished are welcome – leave a comment and I’ll get back to you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.